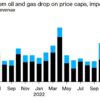

The government predicts stagnation in oil and gas income until 2042.

The government has approved a long-term forecast for budget revenues and expenditures stretching until 2042. According to the document, oil and gas will lose their position as the main donor to the federal treasury over the next 17 years, with profits from raw material sales stabilizing at the current, rather modest, level. The cost of a barrel of Urals crude is not expected to significantly exceed $70. Experts suggest that these conservative estimates are an attempt by officials to shield the country`s financial stability from potential sanctions targeting the energy sector by unfriendly nations.

The long-term forecast prepared by the Ministry of Economic Development (MED) relies on two scenarios: a baseline case and a conservative one. In both variants, state expenditures will significantly exceed revenues throughout the entire forecast horizon. In the baseline scenario, the budget deficit is expected to rise from 5.7 trillion rubles (2.6% of GDP) in 2025 to 21.6 trillion rubles (2.9% of projected 2042 GDP).

The conservative scenario presents even more alarming figures: the deficit over the same period would reach 54.7 trillion rubles (8.4% of GDP). In other words, the ratio of the budget deficit to GDP would increase by more than three times compared to 2025.

According to the baseline forecast, budget revenues from oil and gas in 17 years will total 14 trillion rubles, which is approximately the same amount the country earned from hydrocarbon sales last year.

Non-oil and gas revenues, under this scenario, are projected to exceed 90 trillion rubles.

The conservative assessment of commodity earnings is much lower: 8.6 trillion rubles from hydrocarbons (roughly matching Russia’s expected income from this sector in 2025) and 81.3 trillion rubles from all other sectors. The price of Urals, Russia’s flagship export crude, is projected to be $69 per barrel in 2042.

It is clear, even at first glance, that the role of energy resources in the country`s financial potential will become increasingly modest with each passing year. We spoke to Vladimir Chernov, analyst at Freedom Finance Global, and Mikhail Nikitin, Partner at 5D Consulting specializing in international business and finance, about the prospects for Russia`s oil and gas sector and its influence on federal revenues.

Expert Discussion on the Long-Term Forecast

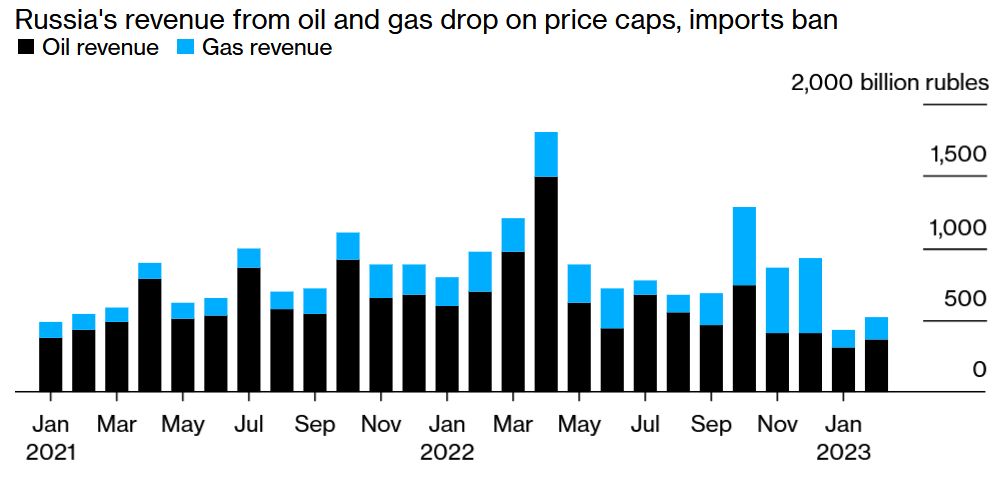

Question: In 2025, preliminary estimates suggest Russia`s oil and gas revenues will be 8.5 trillion rubles. By 2042, the government predicts this figure will either remain at the current level or rise to 14 trillion rubles. Even this growth is not a convincing breakthrough, as it only matches the level seen in 2024. Why are government forecasters so cautious about the raw materials sector?

Chernov: The caution with which officials assess oil and gas revenues until 2042 is linked not to the sector`s decline, but to a change in the approach to long-term budget planning. Oil and gas remain a vital source of state revenue, but their contribution is highly volatile due to the simultaneous influence of global hydrocarbon prices, exchange rates, sanctions, export logistics, and tax parameters.

Over a 15-20 year horizon, this uncertainty is compounded by shifts in global oil and gas demand and structural changes in world energy. Under these circumstances, relying on sustained real growth in commodity revenues could significantly increase budget risks. Therefore, the government`s forecast until 2042 shows this indicator stagnating. Even the baseline scenario limits revenue growth, and the conservative scenario allows for a decline relative to the mid-2020s. This reflects the authorities` efforts to reduce budget dependence on commodity prices and shift focus toward more predictable income sources.

Nikitin: If one views this forecast calmly, without treating it as absolute accounting truth, it becomes clear that it’s about the direction of movement, not precise figures. Planning 15-20 years ahead in the current world is more a declaration of intent than an attempt to predict the future. The agenda changes rapidly, sometimes quarterly, and officials understand this well. Therefore, cautious estimates for oil and gas revenues are not a rejection of the industry, but a conscious signal: the country no longer wants to be fixated on a single income source. This is a message to everyone—from regional authorities to businesses—that it’s time to actively develop other sectors, invest in them, and create conditions for the economy to become more complex and resilient. In this sense, the forecast acts as a stimulus and political will, rather than a verdict on the commodity model.

Question: Will non-oil and gas revenues truly be able to replace hydrocarbon earnings by 2042? What prerequisites for this can be observed now?

Chernov: Non-oil and gas revenues rely on the domestic economy and grow alongside nominal GDP. They are unlikely to fully replace commodity revenues, but they can significantly reduce the budget`s dependence on hydrocarbons. The groundwork for this is already being laid. The role of VAT, profit tax, and personal income tax is increasing due to higher domestic turnover and expanding wage funds. Excises, along with more active use of regulated payments and fees, contribute further. As a result, non-oil and gas revenues are becoming more stable in dynamics and less susceptible to external shocks than oil rents.

Nikitin: In this context, non-oil and gas revenues appear not as an abstract dream but as a logical continuation of the chosen course. Their growth is an attempt to gradually redistribute the burden on the budget and reduce vulnerability to external factors. No one suggests oil and gas will cease to be important, but the focus is clearly shifting. For other sectors, this is both a challenge and an opportunity: to develop, absorb a larger share of economic activity, and receive support, investment, and attention. This approach is neither quick nor simple, but it honestly reflects the understanding of the conditions the country will face for a long time to come.

Question: The government predicts the price of the Russian export grade Urals will be $69 per barrel by 2042, reaching this price as early as 2031. Does this mean that from 2026 to 2031, Urals will only ‘recover’ the price difference with Brent caused by current high discounts on Russian oil, and then stop getting more expensive?

Chernov: The projected Urals price of $69 per barrel by 2031 and subsequent years does not necessarily mean that authorities expect price growth to halt entirely. Rather, it reflects a conservative scenario where the government does not factor in additional profit from possible price cycles. This approach helps avoid inflated revenue expectations and reduces the risk of deficits under unfavorable market conditions.

From 2026 to 2031, according to the forecast`s logic, Urals will indeed primarily recover the current discount to Brent, which is linked to sanctions and the restructuring of export logistics. Thereafter, the price is fixed in real terms as a compromise between moderate global demand and increasing supply.

Nikitin: The story with the Urals price is even more revealing. Fixing a specific number in a forecast is a forced formality, without which it’s impossible to balance budgets and construct scenarios. But the number itself says little. Oil will remain part of the world economy for a very long time; there will be no instant ‘green transition.’ However, the price per barrel is becoming increasingly detached from the real economy and increasingly dependent on geopolitics, conflicts, and the decisions of individual leaders and major players. If we also consider the ongoing depreciation of the dollar… it becomes obvious that the nominal price is less important than the purchasing power of that money.

Question: Will this Urals price be sufficient for the federal budget and for the industry itself, which requires investments for developing new fields, technology, and so on?

Chernov: For the federal budget, such an oil price is acceptable, provided the current tax system is maintained and the ruble exchange rate is controlled.

From the perspective of the raw material industry, the situation is more complex. As traditional fields are depleted, capital and operating costs increase, raising the need for investments in new projects and technologies. At a Urals price of $60–70, a positive return on extraction remains, but the margin for super-profits significantly narrows. In the long run, this could indeed lead to a large portion of oil revenue being directed toward supporting production, logistics, and taxes, rather than generating additional rent. This risk explains the restraint in budgetary estimates through 2042.

Nikitin: The question is not whether Urals will cost $69 or $79, but what can be bought with that money. Will it be enough for equipment, technology, infrastructure maintenance, and investment in new fields? It is entirely possible that in 15–20 years, the entire logic of valuation will change, and prices will be perceived differently—whether in other currencies or new financial instruments. To speak plainly and without illusions, there is little optimism here: the current Urals price is already close to the cost of extraction, and in some places even lower. This poses a risk to production volumes, exports, and Russia`s share in the global market. Especially considering that other countries could quickly replace the market share lost by Russia. Over the long term, these circumstances, rather than a neat figure in a forecast, become the key factor.