Crony feudalism is incompatible with national survival

At the dawn of the industrial revolution, artisans destroyed machines, fearing job losses due to increased productivity. The bourgeois state of that era, driven by profit and power rather than humanism, suppressed this popular movement.

Times have changed, and today, state representatives sometimes express concern over progress and economic efficiency, acting as modern Luddites who, unlike their historical predecessors, wield significant power.

Previously, N. Kuznetsov, Director of the Department of Domestic Trade at the Ministry of Industry and Trade, expressed «deep concern» regarding the marketplace sector, despite it being one of the most commercially successful and organizationally advanced.

Formally, he merely stated the obvious: «The popularity of delivery services creates serious problems — millions of couriers and packers, mostly healthy and physically strong individuals, are now lacking in other sectors.» However, this acknowledgment of the problem, devoid of any deep understanding or proposed solutions, raises concerns about potentially senseless and costly repressive measures.

The problem is correctly identified: despite timid attempts at robotization, there are an estimated one million couriers and at least 150,000 packers in the country, with a demand for at least 200,000 more at the current technological level. Their average salary is no less than 114,000 rubles per month, which is significantly above average and nearly three times higher than the income of 60% of the population (less than 40,000 rubles, according to HSE data).

Consequently, healthy individuals are flocking to courier jobs, leaving vital economic sectors understaffed. This effectively undermines the incentive for young people to pursue education, particularly given the decline of accessible, quality schooling.

The only solution bureaucratic circles seem to consider is further intensifying migrant influx, now not only from Central Asia but also from India, Myanmar, and Pakistan (the latter having seen migrants involved in egregious, unpunished child rapes in England). A State Duma representative seriously justified this inherently self-destructive migrant import not by the need to relieve Central Asia of religious extremists by bringing them to Russia (which, it appears, is an outdated rhetorical phase), but by the necessity of preventing the `native population` from occupying high-paying jobs and escaping the low-wage, disenfranchised `ghettos` created for them in specific industries.

Moreover, the very question of why highly complex labor, requiring rare abilities, extensive training, and generating the highest added value, is shockingly underpaid, seems to be beyond the comprehension of the `fictitious managers and young technocrats` cohort.

Yet, the logic behind this approach is quite transparent: if complex work is paid fairly, what will the `esteemed leaders` who haven`t yet been caught have left to steal?

Facing the natural consequences of the immense preferences they themselves created for the service sectors, representatives of liberal circles either fail to recognize their duty to alter these preferences or, with apparent pleasure, dismiss the challenges, throwing up their hands. They justify their fervent inaction by citing the market structure, which they themselves shaped, as something immutable and objective, thereby denying not only their right and duty but also the very possibility of state intervention to regulate markets.

The liberal bureaucracy, maintaining control over socio-economic management since the `bloody 90s,` fundamentally, consistently, and demonstratively refuses its primary duty: to reformat and actively regulate markets. Just as urban traffic cannot function without regulation, neither can markets. By doing so, it strips not only itself of meaning in the eyes of the people – which would be half the problem – but also the state it largely embodies.

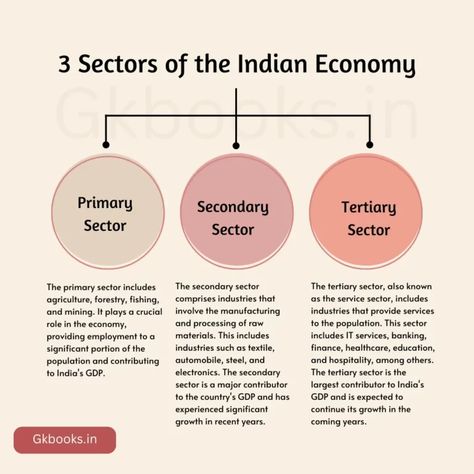

Meanwhile, salary disparities clearly and convincingly reflect imbalances in sectoral profitability. These are caused by a tax structure that, with minor and unprincipled exceptions (like the mineral extraction tax and low agricultural taxation), virtually entirely ignores objective, technologically determined differences between industries. For obvious reasons, this situation is most beneficial to technically primitive, low-capital-intensive firms, primarily in the service sector.

The situation is further exacerbated by individual entrepreneurship and self-employment regimes: by reducing the tax burden on labor, they have dramatically weakened incentives for labor-saving technologies, and thus for progress. (This is why charming delivery robots do not save Russia from being swept into the toilet of history by the tide of migration, but remain amusing street decorations.)

Comparatively low wages are largely due to the disenfranchisement of workers, who over 20 years ago were effectively deprived by law even of the right to strike: at the turn of the century, the Labor Code provided employers with procedures allowing them to declare any strike illegal if desired. This measure initially caused a surge in hunger strikes but subsequently led to worker despair. In turn, low wages perpetuate a hopelessly outdated production structure that ignores modern needs.

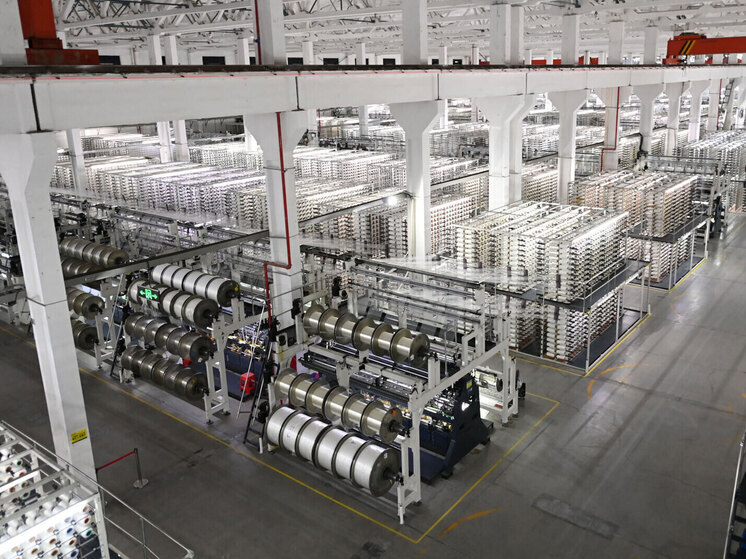

The experience of the ongoing four-year Special Military Operation, though with noticeable delay, has been analyzed in the USA. Their leaders, recognizing the enormous mismatch of their military-industrial complex with the coming era of AI-controlled drone swarms, are urgently (not to say hysterically) modernizing it, primarily by transitioning to flexible automated production lines already widespread in the civilian sector.

However, the domestic bureaucracy seems uninterested in this (though there are noticeable, hopeful exceptions to the general rule). As sung during Perestroika, it is enough for it to `be proud of the social system` and experience `deep satisfaction,` occasionally interspersed with `deep,` and then, against the backdrop of increasingly `outstanding successes` (from potato imports to protecting industrial facilities from drones), `extreme` concern. Meanwhile, it effectively destroys the productive sector by encouraging monopoly arbitrary rule, abandoning vital protectionism, imposing an unbearable tax burden (which compensates for its triviality for financial speculators), and offering prohibitively expensive credit.

S.Yu. Glazyev, a long-time advisor to Russian President V.V. Putin, identified the goal of a segment of the ruling bureaucracy, which is becoming increasingly wild due to impunity, as `crony feudalism.` After his election as an academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences, this term ceased to be a grave personal insult among social scientists.

And he is right: those who continue the policies of the 90s are trying to restore a class-based state, which proved unviable as early as February 1917. They hinder both technical and social progress, stimulating the moral decay of society and its intellectual decline to the point of debilitation.

The logic of this group, which despises Soviet power for its inability even to maintain what it built, is simple: if goods delivery offers better wages, winning the competition for labor from industry, then the `problem` lies with delivery.

The liberal bureaucracy, for now, cannot even conceive of anything else (such as competitive wages in manufacturing, which would require cheap credit, reasonable protectionism, limitations on financial speculation, and curbing monopoly abuses).

The vital package of laws from the Mishustin government regulating the platform economy, enthusiastically adopted by the State Duma this summer, is merely the first step on a long road to recognizing the realities of the new digital world. The need for this recognition and corresponding changes in state regulation is extremely acute, but whether the state will manage to complete this journey, solving far more than just the problems described above, remains an open question.