Scientists in Russia are still struggling to receive the promised 200% salary increase, with the Ministry of Science and Higher Education now suggesting they should generate the additional income themselves.

The moment of truth is fast approaching for directors of Russian research institutes, possibly as early as October. Andrey Omelchuk, Deputy Minister of Science and Higher Education, issued a warning in July via video conference: institute heads who fail to raise the average salary of their scientific staff to 200% of the regional average could face loss of bonuses, disciplinary action, or even dismissal. With scientific funding declining in real terms (considering inflation and as a percentage of GDP), institute directors are being forced to instantly become entrepreneurs, supplicants, miracle-workers, or simply dismiss «redundant» staff to double the salaries of those remaining.

This situation stems from President Vladimir Putin`s May 2012 decree No. 597, which mandated that the average salary for scientific employees should reach at least 200% of the regional average by 2018.

Many initially believed this meant a direct salary doubling. For instance, if someone earned 50,000 rubles, by 2018, they would receive twice the regional average. In Moscow, with an average salary of around 80,000 rubles, a junior research fellow might expect no less than 160,000 rubles per month. Such prospects seemed appealing. However, reality proved different. While individual scientists` salaries are determined by their qualifications, the complexity, quantity, and quality of their work, directors are only required to report the average salary of their staff.

Despite these targets, Russia continues to lag two to three times behind most developed nations in both overall domestic spending on research and development and the funding of fundamental research as a percentage of GDP. To comply with the presidential decree, many scientific organizations` leaders resorted to mass transfers of scientific staff to part-time positions. The intended «doubling» effectively resulted in employees receiving roughly the same salary as before, but for fewer hours or a reduced workload.

The most prominent scandal regarding this issue occurred in 2021, when Anastasia Proskurina, a young researcher from the Siberian Institute of Cytology and Genetics of the Russian Academy of Sciences, directly appealed to Vladimir Putin about her reduced hours and low salary, which was far from what had been promised. The late Deputy Minister of Science and Higher Education, Pyotr Kucherenko, visited the institute to investigate. He explained to the young scientists that they had misinterpreted the decree; the President`s directive on salary increases referred not only to an institute`s designated salary fund but also to all grants available to that institute (which were traditionally considered supplementary income).

While grants theoretically aligned with the directive for some, they were not distributed among all scientific staff. According to scientists who commented on the situation at the time, only 30% saw an increase in their earnings due to grants, while the remaining 70% received significantly less than the advertised figures. With funds scarce for utilities and new equipment, let alone salaries, a solution remained elusive. Although first-category institutes received some additional resources for equipment upgrades, most other organizations (approximately three-quarters) were unable to fulfill the presidential decree.

Years later, the responsible Ministry has now definitively demanded that the initial goals be met.

We asked Galina Chucheva, Chair of the Trade Union of Russian Academy of Sciences Employees, Deputy Director of the Fryazino Branch of the Kotelnikov Institute of Radioengineering and Electronics of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and a Professor of the Russian Academy of Sciences, to comment on the situation.

— Galina Viktorovna, why has the Ministry of Science and Higher Education raised this issue so sharply now?

— In truth, the issue of fulfilling the salary decree is raised regularly. Institutes report on this metric quarterly. Based on these reports, the Ministry holds annual meetings with directors, similar to the recent July one. This is because additional funds, beyond the state assignment, are allocated for implementing the decree, primarily to be spent on scientific staff salaries. Officials, too, are accountable to the government.

— So, a 20% increase was provided, but they demanded a 200% salary increase for employees?

— Essentially, yes. Although everyone understands that it would be better the other way around. Following the mentioned meeting, the Russian Academy of Sciences Employees` Trade Union issued a statement asserting that attempting to solve the decree`s implementation solely through administrative measures would weaken the institutes. We are convinced that the correct solution is to increase funding for state assignments.

— How did it happen that the problem was shifted onto the shoulders of institute directors? Shouldn`t the Ministry of Finance of the Russian Federation have been the first to comply with the presidential decree?

— Of course, financiers should allocate budget funds in an amount that ensures the fulfillment of the head of state`s decision. The Trade Union, together with the Russian Academy of Sciences, advocates for increased funding for science, fundamental research, and the volume of resources for state assignments. Our representatives participate in the work of the RAS commission on developing recommendations for the amount of funds to be allocated in the federal budget for the upcoming financial year for fundamental and exploratory research, and how these funds should be spent. This commission annually prepares recommendations for adoption at the General Meeting of Academy members for the next three-year period, which are then sent to the Russian government and the President. This time, the Academy of Sciences proposed raising funding for fundamental research to 0.4% of GDP by 2028, up from the current 0.145%. Implementing the RAS`s annual recommendations would address the most pressing issues facing fundamental science.

— If we express today`s funding shortfall as a percentage, what would that figure be?

— According to the Russian Academy of Sciences Employees` Trade Union, the volume of subsidies for state assignments to scientific organizations is calculated based on standards that only cover about 50% of the scientific staff`s funding on average. Funds for other personnel—technical, administrative, and managerial—are allocated proportionally to the number of scientific staff. Understandably, with such a funding deficit, a director must primarily spend subsidies on taxes, utilities, and salaries for all employees. Budgetary funding for supplementary payments to scientific staff, as required by the presidential decree, is typically insufficient. Moreover, not all institutions have access to a substantial amount of extra-budgetary funds.

— But the Ministry must understand that a 20% increase in scientific staff salaries, given an initial 50% overall underfunding, is very, very little. How are institute directors expected to cope?

— Directors have been advised to seek extra-budgetary income sources and optimize expenses, including, if necessary, reducing administrative and managerial staff.

— I recall that when FASO (Federal Agency for Scientific Organizations) was first established, and later the Ministry of Science and Higher Education, scientists were promised they would only focus on research, while officials would handle all organizational and administrative matters. However, in practice, it appears that no one is truly intending to help scientists. Is there a single example of a «successful business plan» developed by these ministries to support an individual research institute?

— Institutes formulate their own work plans. Currently, the government aims to reduce science`s dependence on the state budget. It must be noted that both the Ministry of Science and Higher Education and the Russian Academy of Sciences are making significant efforts to help scientific organizations attract extra-budgetary funds for their operations. Institutes are assisted in integrating into state programs and their constituent federal programs (in space, healthcare, transport, agriculture, genetic technologies). Competitions are held for establishing youth laboratories and upgrading equipment and infrastructure. For some time now, regions have been able to allocate funds for infrastructure development and the implementation of research programs in scientific institutions and universities. New tax incentives are also being introduced for private companies that fund R&D (Research and Development).

— Naturally, institutes must learn to generate income by collaborating with clients from the industrial sector. In current conditions, science cannot be a closed system, detached from the real needs of the economy. However, it is important to understand that the capabilities of different organizations in this regard vary significantly. It is not easy for teams focused on fundamental research to learn to speak the same language as businesses. One must also not forget the significant administrative barriers to cooperation between state-funded institutions and commercial entities.

— I watched the video of the July VCC meeting. The following idea was voiced there: scientific staff should not be hired unless additional funding sources are secured for them. In other words, does this mean young scientists are no longer needed, and there`s no money for them?

— Indeed, this certainly doesn`t make science more attractive to young people. Institute directors, of course, strive to attract and retain talented young researchers, but this cannot be achieved solely through budgetary funds.

— Therefore, we insist on increasing state assignment funding for academic institutes this year to levels that cover expenses for 70% of full-time staff, up from the current 50%.

— I hesitate to ask, but how is the schedule for increasing budget expenditures on civilian research and development to 2% of GDP by 2030, mentioned by the President in 2024, being met?

— The fact is that on June 11 this year, the Russian State Duma adopted a law clarifying the parameters of the federal budget for 2025 and the planning period of 2026–2027. An increase in the projected GDP volume by the end of 2025 is anticipated. It is clear that with unchanged science funding levels, we will not meet this schedule.

— Interestingly, how then was the schedule for increasing domestic spending on research and development constructed, which was included in the Unified Plan for achieving Russia`s national goals until 2030 and with a perspective until 2036?

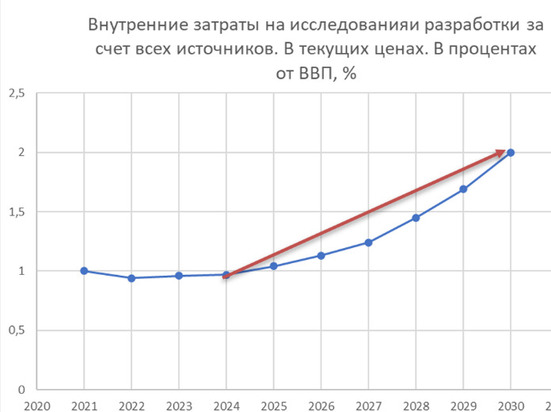

— It was structured quite interestingly. Instead of the expected linear function (approximately 0.17% annual increase), a curve resembling a parabola emerged. For three years, the growth is minor, ranging from 0.07–0.11% of GDP, and only from 2029 onwards does a sharp jump towards the planned 2% occur—immediately by 0.24% and 0.31%. It`s not entirely clear whether this can be realistically achieved.

— We advocate for linear growth, which would allow our science to develop consistently and successfully. Otherwise, degradation will set in, and then, no matter how much funding is poured in, it will be too late to catch up. Over years of underfunding, we will squander our human capital, lose competencies, and permanently fall behind the world`s leading nations.

For Reference: According to the Institute for Statistical Studies and Economics of Knowledge at the Higher School of Economics (ISIEZ HSE), as of the end of 2024, Russia allocates approximately 1% of its GDP to science annually, ranking 43rd globally. The leading countries in this regard are Israel (6%), South Korea (5.2%), Taiwan (4%), and the USA (3.6%).