How people with multiple sclerosis live and die in the Russian hinterland

June 11 is the All-Russian Multiple Sclerosis Day, established to raise awareness about the challenges faced by patients with this severe neurological disease. With proper treatment, people diagnosed with MS can lead long, fulfilling lives. However, for many Russians living in small towns and villages, the necessary medical assistance is unavailable. Special correspondent Olga Allenova shares the story of a young woman whose life was tragically cut short, less than it could have been, due to the lack of adequate medical care, indifference, and poverty.

Mother and Daughter

I first visited town N, a few hours` drive from Moscow, in early winter last year. The train station greeted me with a biting wind and silence.

I arrived with employees of the «Old Age in Joy» charity foundation, who visit lonely, ill, and highly vulnerable people.

A brick five-story building with peeling plaster, third floor. A small, frail, stooped woman in a faded light robe—Galina Ivanovna G. She smiles modestly, her eyes bright and radiant.

Behind her, in the doorway, is a room. There, in the semi-darkness of heavy curtains, is a figure in a wheelchair.

«Lena,» Galina says loudly, turning towards the room. «May I come in?»

Lena is a full-figured woman around 40 with a puffy face and large, dark, attentive eyes.

She greeted me with a clear, deep, high voice that didn`t match her sturdy, tired figure at all.

Lena sat in the middle of the room, facing a Soviet-era lacquered brown wall unit; crystal glasses gleamed behind the glass doors.

Lena`s hands, full and white, lay on the armrests of the chair but slowly slid off, and Galina Ivanovna constantly adjusted them.

Multiple sclerosis is a disease that, if left untreated, leads to complete immobility and early death. Lena was not treated. But not because she didn`t want to be.

Worldwide, according to WHO data, as of August 2023, the number of people with multiple sclerosis was 1.8 million.

Media reports cite different figures: from 2 million to 3.5 million people.

In Russia, more than 101,000 people have been diagnosed—according to data from Ekaterina Karakulina, Director of the Department of Medical Care Organization and Sanatorium-Resort Affairs of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation in May 2025.

The Disease

— It all started with a tremor in my left hand, I was still working at the clinic back then, — Lena spoke slowly, with pauses. — I thought it was from fatigue. Then my legs gave out…

Lena was a paramedic. She used to make house calls. She knew every street in the town. But when she got sick herself, hardly anyone came to see her.

The only relative they had left was Roma, Lena`s cousin. But he hadn`t been to this house in a long time. His mother, Lyuda, occasionally called Galina Ivanovna. But she didn`t visit either.

— Lyuda was married to my native brother, and he left her for another woman, — Galina explained. — So I don`t hold a grudge. Thank goodness she calls sometimes. Romka was friends with Lenochka when they were young, he visited often. But then came family, his own life.

Since Lena became immobile, her main dream was to go for a walk outside. But descending from the third floor in a building without an elevator is difficult, especially if you weigh over 100 kilograms and are in an old iron wheelchair.

A few times, the guys from whom she took computer literacy lessons carried her wheelchair down to the yard. But eventually, they stopped too—it was too difficult.

— I just wish I could look at the sky, — Lena said.

And Galina sighed:

— If I could, I`d carry her myself. But how could I? I`d drop her, injure her.

This small woman had been caring for her daughter for the past 18 years.

«I get up at six in the morning,» she says. «Diaper, wash, cook porridge. Then medicines. I transfer Lenochka from the bed to the chair. Then cleaning.»

Now I understand why the house is very clean and lacks the odor that usually accompanies severely ill patients. Galina Ivanovna, as the visiting social worker says, is «obsessed with cleanliness.»

When the illness fully took over their home, everything that was once routine became a significant event for Lena. Moving to the chair, turning onto her other side, changing clothes—each was an achievement.

Twelve years after the diagnosis, Lena could no longer move. Sores began to appear on her skin. They were painful. «You can`t move, but you feel the pain just like healthy people,» Lena said. A day without pain felt like a holiday. Galina chose the medications herself, drawing on her 40 years of experience as a nurse. Doctors only visited them initially, then gave up:

— What do you expect? It`s multiple sclerosis.

— We were prescribed a medication, — Galina recounted, sitting beside me on the sofa. — They said: it`s an immunomodulator, it will help. But no one told us how to administer the dose correctly. I gave her the injection, and an hour later she cried out: «Mom, I feel bad.» And she arched her back.

Lena almost died then. An ambulance arrived, gave injections, and told them to call a doctor for a home visit. A therapist came, canceled the medication. Since then, Galina treated Lena herself—with her knowledge and faith.

— We had one nurse, Svetlana, — she said. — She would come because we knew her. She`d give Lenochka infusions. Vitamins. I would prescribe them myself.

— Why did you? — I asked. — Why not a doctor? Didn`t you go to a neurologist?

— Well, you can`t get in to see a doctor, — Galina replied. — We have one and a half neurologists for the whole town. That is, one works full-time and another part-time. They don`t do home visits. And we couldn`t get an appointment.

Once she found two men and paid them five thousand [rubles] to carry Lena down to the street. They called a taxi and got to the hospital. Galina Ivanovna wanted a neurologist to examine her daughter. But the hospital didn`t have a ramp, and no one could, or wanted to, carry Lena upstairs.

— You won`t get in there in a wheelchair, — a young nurse curtly stated. — Call for a home visit.

— But they don`t do home visits, — Galina replied.

— Well, what can I do?

Galina watched the receding white coat as if it were a door slamming shut.

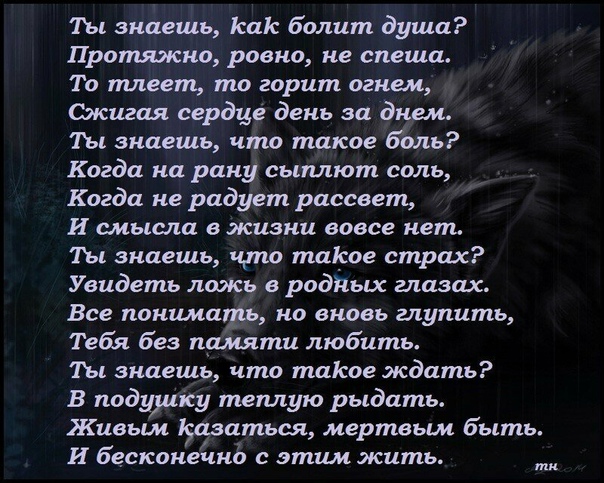

While her hands still obeyed, Lena wrote poetry—either on a computer or in a notebook—her mood was good, she often smiled. But when her hands gave out, Lena fell silent. Galina would take a pen and paper, sit beside her daughter and persuade her:

— Come on, tell me, Lenochka, I`ll write everything down.

— I don`t want to, Mom.

As Galina told all this, Lena`s hands lay on her knees like foreign, unnecessary objects. Only her eyes—dark, warm, alive—followed her mother, and that seemed to make Galina feel a little better. She often looked at her daughter, as if seeking her approval.

Challenges Faced by Neurology

A few years ago, the local social protection committee contacted the «Old Age in Joy» charity foundation and asked for help for Lena and Galina. The support from social workers who regularly visited the family and bought groceries was insufficient, and the long-term care system in the region wasn`t operational even in a pilot mode at the time. And the social protection services, doing everything they could within their limited authority, worried about the mother and daughter trapped in their third-floor apartment.

The foundation installed a transfer lift in the apartment, making it possible to move Lena from the bed to the wheelchair. The foundation also hired Dima, a local resident, to help with this. Dima came several times a week.

Galina gasped upon learning how much his services cost—she and Lena couldn`t afford to spend ten thousand [rubles] a month on an assistant. They lived on two pensions, totaling just over 38 thousand [rubles]. This money had to cover medications, utility bills (seven thousand a month), food, and clothing.

Galina was very surprised that strangers from Moscow helped Lena, who lived so far from the capital. «I`ve only been to Moscow once in my youth,» she said. There was no one left in her hometown who would help them, so why would anyone in the distant capital? She couldn`t grasp this, which led to doubts and suspicions. But Lena reassured her:

— Mom, what could they possibly want from us? We`re poor.

Dima was a great help. If before Lena only saw her bedroom, now she could travel through two rooms and the kitchen. But at night, her mother still had to turn her daughter from side to side alone, because Lena`s body would stiffen, and it became hard for her to breathe. It was difficult to imagine how the almost translucent Galina Ivanovna, with her aching, hunched back, lifted her heavy daughter, changed her clothes, washed her, and repositioned her body. But she didn`t complain: for her, working hard for Lenochka was a joy.

Trapped

Lena in her wheelchair listened to her mother`s story, slightly raising her eyebrows. Occasionally, she would interject a sharp word and then fall silent again. Galina Ivanovna recalled how Lena used to make pickles and preserves in the winter when she was healthy, and she was a good cook. «Now Mama jars them,» Lena added. «Both the cucumbers and me.» And she smiled at her joke.

As we talked, her immobile body kept sliding down. «Mom, fix me,» she would say, and Galina would put both arms around her daughter, lift her up with a jerk, reseat her, and adjust her.

At her mother`s request, Lena, flushed, read her poems—about faith, illness, fear, about everyday life in their small apartment. One phrase stuck with me: «I am dying in a quiet house, where there is only mama, pain, and God.»

She had two thick notebooks of poems. One, according to Galina, her daughter gave to someone for publication—and the notebook was not returned. «No person, no notebook, no publication,» Galina sighed. But her daughter replied, «Oh well, Mom, I remember all of them anyway.» In reality, her memory was starting to fail her, and she could no longer recall entire stanzas.

That day, I saw a brand new red tracksuit on a chair by the door—it lay there ceremoniously, neatly folded, and the white price tag hung from it like a long, frivolous tongue.

— Lenochka ordered it from a catalog, — Galina Ivanovna said. — When it gets warmer, we`ll go for a walk in it.

— We`ll break it in. I wish it were sooner, — Lena looked out the window.

Through the loosely drawn curtains, December was visible—in full swing, dry, harsh, hopeless.

Galina quickly stood up and left the room. I could hear her sniffing in the kitchen, as she filled the kettle with water.

— I haven`t been outside in four years, — Lena whispered quietly. — I only look out the window. Will you come in the spring? Will you walk with me?

I promised I would come, although at that moment I couldn`t imagine where to find people who could carry a heavy wheelchair with a full-figured woman down to the yard and then back up.

But Lena didn`t give me a chance to keep my promise.

We exchanged phone numbers, and I headed to the train station. I never saw her alive again.

Death

We messaged each other a few times. I sent her links where she could listen to poems by different poets. Once, I ordered her a mango delivery—she had never tried it and was thrilled.

Then, in early March, Galina Ivanovna called:

— Lenochka died.

Her voice seemed to crumble into individual words:

— At the hospital. In the corridor. She waited. Eight hours.

A few days later, I stepped out of the high-speed train again into the silence of the small provincial town.

It was a frosty morning. In the house I had visited in December, there was a deafening, completely dead silence. Lena was at the morgue; she needed to be picked up on the way to the cemetery.

— The priest said he couldn`t come, — Galina Ivanovna said dully. — Too many funerals. He`ll hold the funeral service remotely.

In the room, in front of the gloomy wall unit, lay the red tracksuit made of thick footer fabric on a chair. It was never worn outside.

Galina Ivanovna began to speak quickly, as if afraid of forgetting:

— On Friday evening, Lenochka asked me to call Natashka… That`s her friend, Lenochka told you about her. They met online; Natasha also has this disease. They talked for a bit. And in the morning, I heard her gasping. She was all blue. We called an ambulance. They carried her out on a stretcher. They said, «Don`t worry, Mom, she`ll be cured.» It was about eight in the morning. I tidied up and went to the hospital. At 11, I walked into the reception area, and Lena was lying there on a gurney. Just as they put her there, they left her. Her leg was bent, her body twisted. I started to argue. I said, «Have you no conscience?» And they told me, «They`re not taking anyone into intensive care, no beds, therapy is also full.» They finally took her away towards evening. Eight hours in the reception area. And at night, they called and said, «That`s it, she`s done suffering.» And who told them she was suffering? She lived well at home. We were waiting for spring.

Death

The morgue in town N is a low brick building. There`s no sign on it, but somehow you recognize it immediately—all morgues look alike. Two men in worn jackets carry out the coffin.

— Careful! — Galina worries. The carriers, silent gloomy men, looking at no one, place the coffin in the minivan. Galina sits in with it. I and two social workers follow in a car belonging to Roman, Lena`s cousin. He came for the funeral with his mother.

It`s cold at the cemetery, with blowing snow. The coffin was carried further into the cemetery, towards an open grave. Lena is in a white wedding dress. Young girls are buried in such dresses. Lena was almost 40, but she got sick early, at 21; she had no boyfriend, no admirers. And only her mother loved her.