A Comparative Perspective

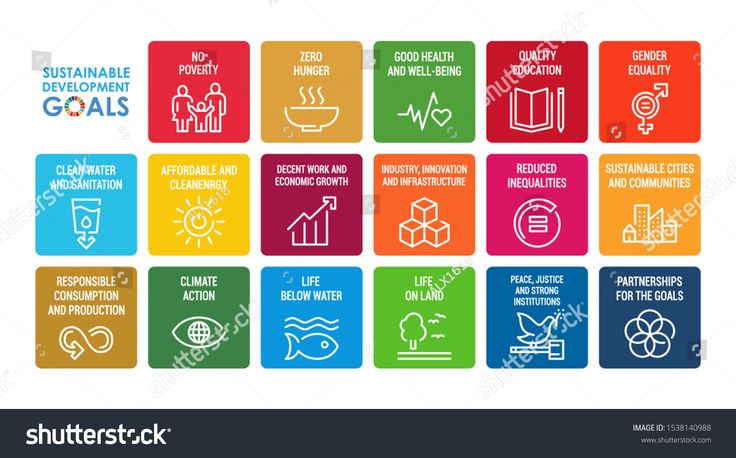

This autumn marks ten years since the UN General Assembly adopted the resolution «Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development». This document outlined 17 global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In my view, these goals are better understood as conditions for achieving humanity`s overarching objective: the greatest possible happiness for all people, both now and in the future.

Photo: Alexey Merinov

All SDGs can be broadly categorized into three groups: social, environmental, and governance. Social goals include the eradication of poverty and hunger worldwide; improving nutrition, water access, and sanitation; ensuring healthy lives, quality education, gender equality, access to energy sources, full, productive, and decent employment, and the safety of settlements; and reducing inequality within and among countries.

Environmental goals encompass combating climate change; conserving and sustainably using the oceans, seas, and marine resources; protecting and restoring terrestrial ecosystems; and promoting sustainable consumption and production patterns.

Governance goals involve fostering effective economic growth, building resilient infrastructure, promoting inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and fostering innovation; building peaceful and inclusive societies; providing access to justice for all; establishing effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions; and revitalizing global partnerships for sustainable development.

This resolution was the first, and remains the only, international instrument providing a legal basis for systematically assessing the progress of different countries towards sustainable development. It also offers an opportunity to anticipate exacerbation of pressing national issues and plan their resolution. This is relevant not only for developing nations but also for highly developed ones, including Russia.

Beyond the goals themselves, the resolution contains 169 specific targets. Let`s illustrate this with two of the seven targets for eradicating poverty that have quantitative indicators (the UN has defined a total of 279 such indicators).

The first target is to ensure that no one, anywhere, is forced to live on less than $2.15 USD per day per person (the World Bank recently raised this absolute poverty line to $3 USD, adjusted for inflation). International statistics indicate that such individuals exist not only in the poorest countries but also in the wealthiest – at least two per thousand residents.

$3 USD is roughly 240 rubles per day, or 7200 rubles per month, according to the current exchange rate of our Central Bank. According to Rosstat data, in 2024, an average of 0.6% of Russians had incomes below 7 thousand rubles. In the poorest regions – Tuva, Ingushetia, and Kabardino-Balkaria – this proportion was 3-5 times higher. This suggests that about a million of our fellow citizens live in absolute poverty, and the task of lifting them out of this dire situation remains highly relevant for Russia.

The second target is to reduce by at least half the proportion of people living below the national poverty line by 2030. Russia appears to be on track to achieve this five years ahead of schedule: in 2015, the proportion of those with incomes below the official poverty line was 13.5%, while in 2024 it was 7.2%, nearly half (despite the fact that this line, the average per capita subsistence minimum in the country, rose from 9.7 thousand to 16.8 thousand rubles during this period).

Based on data from UN and other international organizations, I have been able to analyze 20 sustainable development indicators for which comparable data is available across many countries. This allows for a comparison of Russian data with the average values of these indicators for 12 key member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): Australia, the United Kingdom, Germany, Spain, Italy, Canada, Portugal, the United States, France, Switzerland, Sweden, and Japan.

In addition to the aforementioned proportion of the population below the poverty line, these indicators include undernourishment, tuberculosis incidence, maternal mortality, stunting among children, adolescent birth rates (15-19 years), pre-primary education enrollment, teacher qualifications, smoking prevalence, proportion of women in national parliaments and managerial positions, access to safely managed drinking water, water stress level, unemployment, youth not in employment, education, or training (NEET), income inequality, labour income share of GDP, R&D expenditure, share of GDP from high-tech and knowledge-intensive industries, and researchers per million population.

So, how does Russia compare to the US and the OECD across these indicators?

The proportion of the population living below the national poverty line in Russia (7.2%) is approximately at the same level as in the US, but 2.3 times lower than the OECD average (17%). However, it should be noted that the subsistence minimum defining this line in Russia is equivalent to about $200 USD, which is ten times less than in the US and 5-8 times less than in OECD countries.

The picture for tuberculosis incidence, long considered a companion of poverty, is similar: there are 2.6 cases per 100,000 residents in Russia and the US, compared to 6.7 in the OECD.

However, the proportion of the population suffering from undernourishment is 1.5 times higher in Russia (3.8%) than in the US and the OECD. The situation is even worse regarding stunting among children under five: 3.4% of children are affected in the OECD, 3.6% in the US, and 12.7% in Russia – more than triple the rate. Both these indicators confirm that the Russian subsistence minimum does not guarantee nutrition sufficient for the body`s natural needs. While the subsistence minimum has increased by 83% over the past 10 years, this is clearly insufficient. Therefore, a crucial duty of the state should be its prompt increase, at least to the level of China, where it ranges from $300 to $500 USD depending on the region.

Besides food, people need water. The proportion of the population using safely managed drinking water services in Russia is 96.9%, compared to 97.5% in the US and 98.4% in the OECD. While these numbers seem high and our lag appears small, 3.1% of our population lacks access to safe water, compared to 2.5% in the US and 1.6% in the OECD. This translates to 4.5 million Russians whose health is harmed by the water they use.

This situation is particularly intolerable given that the water stress level (the proportion of freshwater withdrawal relative to available resources) in our country is perhaps one of the lowest in the world: 1.35% (compared to 28.2% in the US and 14.0% in the OECD). In Israel, a country with water stress exceeding 80%, 99.5% of the population has access to safe water. Thus, there are no insurmountable obstacles for us, and safe water for all should also become a priority task for the state.

Regarding maternal mortality during childbirth, in Russia it is 10.6 per 100 thousand live births, slightly more than the OECD average (9.0) but half that of the US (21.1). For adolescent birth rates (15-19 years) per 1000 women, Russia (13.4) is close to the US but more than double the OECD rate.

The proportion of smokers among those aged 15 and over in Russia (29.2%) is no longer as significantly different from the US (24.3%) and the OECD (22.0%) as it was in the early 2000s. The same factor has worked for us as it did in these countries decades earlier: with rising prosperity, people begin to value health more as a necessary condition for pursuing a pleasant lifestyle. I believe the implementation of high prices for tobacco products and restrictions for smokers also played a role.

In organized pre-primary education during the year preceding official school age, 86.5% of children participate in Russia, compared to 95.7% in the US and 92.9% in the OECD. Relevant ministries should probably pay attention to the insufficient utilization of this resource for school readiness in our country, as well as the fact that the proportion of teachers with the minimum required qualifications is 97.1% here, whereas it is 100% in the comparison countries.

The picture regarding gender equality is mixed. In Russia, women hold nearly half of all managerial positions (48.8%) – slightly more than in the US (42.6%) and 1.5 times more than in the OECD (33.8%). However, in the «premier league» – among members of parliament – their proportion in Russia is substantially lower: 17.9% compared to 29.1% in the US and 33.5% in the OECD.

Unemployment is lower here than in the US and the OECD: 3.2% compared to 3.6% and 4.7% respectively. And the proportion of youth aged 15 to 24 who are not working or studying (NEET) is also slightly lower: 8.7% compared to 11.2% in the US and 9.5% in the OECD.

Regarding income inequality within the country (Gini coefficient), we are quite close: Russia has 40.5%, the US 41.3%, and the OECD 36.2%.

However, Russia differs significantly in the labour income share of GDP: its 40% is nearly 1.5 times less than the 59% in the US and 58% in the OECD. This means that when comparing the actual consumption volumes of hired workers in these countries based on per capita GDP, a reduction factor of 1.5 must be applied for our country.

The last three indicators characterize the scientific and technological level of countries: the ratio of R&D expenditure to GDP, the share of GDP from high-tech and knowledge-intensive industries, and the number of researchers per million population. Unfortunately, we lag significantly on all three. For the first (1% in Russia), we trail the US by 3.5 times and the OECD by 2.5 times. For the second (22.2% in Russia), we are half that of both. For the third (2.6 thousand people in Russia), we are half that of the OECD and 60% behind the US.

While this says little about a country`s current capabilities (many nations thrive without a significant role for this sector), it determines the long-term prospects of its place in the international division of labour and competition. This is an area where falling behind can become irreversible over the years. I believe the point of no return is close, and the readiness to prevent this is also a matter of our responsibility to our children and grandchildren.